Recently, a well-known Orthodox monastic and academic shared some of her thoughts on 1 Corinthians 5:9-13, which passage I will now quote:

I wrote to you in my letter not to associate with sexually-immoral people; not at all meaning the sexually-immoral of this world, or the greedy and robbers, or idolaters, since then you would need to depart from the world. But rather I wrote to you not to associate with any one who bears the name of brother if he is guilty of sexual immorality or greed, or is an idolater, reviler, drunkard, or robber—not even to eat with such a one. For what have I to do with judging outsiders? Is it not those inside the church whom you are to judge? God judges those outside. ‘Drive out the wicked person from among you.’

This monastic stated that she does not understand this passage of Scripture, nor does she “relate to St. Paul’s words, as he phrased them in the first century,” to wit: St. Paul’s injunction to judge those inside the church. In her own words: “So I’m wondering, – if all these are to be ‘driven out from among us,’ – then who from among us would be left?”

Before I continue, I want to be completely fair: it is by no means a sin to admit that one does not understand a passage of Holy Scripture. And this monastic was quite clear that what she went on to say (which I will quote and address below) was said “cautiously,” and that she is quite open to being corrected. So this article is not at all intended as a condemnation of this sister in Christ.

With that said, I think the point of view which she voiced is rooted in certain modern assumptions — assumptions which are as widely prevalent as they are vitally important for us to understand as Orthodox Christians. And so I want to take this opportunity presented by her comments to try to get to the bottom of things.

On the most basic level, I want to first point out that — unless I am very badly mistaken — St. Paul’s injunction in 1 Corinthians does not apply to every single person who is guilty of the sins that he mentions. Were this the case, our monastic friend would be quite right to ask: “who from among us would be left?” But in fact St. Paul is referring to those who call themselves Christians while remaining obstinate and unrepentant in their sins. To be a sinner is no obstacle to being a Christian. But to defend our sins — or even more, to take pride in our sins — is a very great obstacle to our Christianity, which after all consists precisely in our repentance.

This distinction is not at all an academic one. Indeed, we are witnessing a veritable renaissance of pride in pagan vice — even, alas, among those who publicly profess themselves to be Christians.

Yet even with this distinction made, I suspect that our monastic would nevertheless not “relate to St. Paul’s words, as he phrased them in the first century,” and would continue to feel discomfort with the idea of judging or cutting off from ourselves Christians who insist that there is nothing wrong with their sins.

And I think that there are also very many of us who feel this same discomfort. Many of us converts were first drawn to the Holy Orthodox Church because She preaches a God of mercy and love, rather than the harsh, vengeful, and juridical deity which Western Christianity has often portrayed. So any call from the Church that contains anything other than our idea of mercy is deeply distasteful to us.

But I chose my words deliberately just now: “anything other than our idea of mercy.” What is really at issue here is that we have unconsciously absorbed the definitions and ideas of the prevailing culture when it comes to words like “mercy” and “humility” and “love.” What is really at issue is that we find St. Paul’s words offensive to our modern sensibilities, and especially to our modern conviction that nobody has any right whatsoever to tell another human being how they ought to live.

Again, this is eminently understandable. Too many have been alienated by a Christianity distilled into nothing more than a set of misunderstood — and therefore apparently arbitrary — demands. And so we are increasingly wary of demanding anything from anybody — even from our fellow believers. We are afraid of driving people away. And so when St. Paul explicitly tells us to drive them away when they refuse to repent, we simply do not understand.

This phenomenon has given rise, in the mind of our monastic friend, to a certain theory:

Today, in the 21st century, the Church is much stronger, and able to “carry” those of us who are the drunkards, the greedy, the sexually-immoral, and the revilers and idolaters, and to admit us to her “table,” without being diminished. Because the Holy Spirit has been at work, and has made progress, in the Church, for many generations since the first century. I don’t subscribe to what Fr. George Florovsky has called the “Theology of Demise,” which sees the Church as going downhill, after the “Golden Age” of the Fathers. No, we are stronger today, glory be to God, and we’ve been brought closer to the ethos of our Lord Jesus Christ, Who “ate and drank” with us sinners, without this diminishing Him. So we’re far less peevish about admitting “sinners” to our table, including ourselves, because we’ve become stronger in our faith in Him, Who presides over His “table.” That’s the way I see it, mistaken as I may be, as I say: Glory be to God, for our today.

Although I certainly sympathize with the inclination to be as charitable to others as possible, this is where I have to get off the bus. When we encounter a contradiction between the words of the Apostles and our own view of what constitutes moral and loving behavior, the absolute last thing we should do is assume that we are so far advanced in holiness and sanctity that we ought to simply ignore the words of Apostles entirely on the grounds that they have become “outdated.”

Whig history is a dangerous animal, and never more so than when it is ecclesiastical history that is in question. When we assume or postulate that discrepancies between our current condition and that prescribed by the Apostles and Holy Fathers is a result of our progress rather than our falling short of that lofty standard, we alienate ourselves from the spirit — and at worst, the very possibility — of repentance. When we assume that the problem is with the wisdom of the Church rather than with our own sense of truth and morality, we become no longer the children of the Church, but rather Her judges. That we make various excuses for the irrelevancy of Her counsels (and thereby backhandedly denigrate the spiritual caliber of our mothers and fathers in the Faith, compared to whom we have “made progress”) does nothing to mitigate the horror of having come to such a pass.

And having thus alienating ourselves from the authentic teachings of the Faith, we turn out to have accomplished precisely the opposite of what we set out to do: we have not drawn people to Christianity, but rather driven them away from it. This can be seen quite easily by examining any of the countless churches that have embraced this “modernization” of Christianity: these churches now stand all but empty.

I recently saw an interview between Jordan Peterson and the Roman Catholic Bishop Robert Barron which gets to the heart of this phenomenon:

Peterson here speaks (as is his wont) the unpopular but extremely necessary truth:

Love is a terrible thing… if you really love someone, you can’t tolerate when they are less than they could be. It hurts. And so, when someone comes into the Church, and it’s all “forgiveness,” there’s no care there… What’s required is a re-emphasis on the potential nobility of the human being, and the moral responsibility to make that nobility a reality…. We’re afraid of hurting people’s feelings in the present, and willing to absolutely sacrifice their well-being in the future. And that’s the sign of a very immature and unwise culture.

He’s absolutely right about this. In our emphasis on mercy — humanly understood — we have forgotten that it is indeed “a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God” (Hebrews 10:31). And we “have forgotten the exhortation which speaketh unto you as unto children, My son, despise not thou the chastening of the Lord” (Hebrews 12:5) — there is scarcely a verse in all of Scripture more needful for our generation than this one.

We have forgotten these things because we have forgotten that there exists such a thing as love that is willing to risk pain in pursuit of healing, that is willing to use even suffering as a means of salvation. In short, we have forgotten the Cross, and the God Who in His surpassing love was willing to be crucified upon it, and Who called each and every one of His disciples to nothing less than that same suffering in pursuit of that same measure of self-emptying love. No, we are a generation of opiate addicts and helicopter parents, and we have instead made for ourselves a god in our own image and after our own likeness.

And that’s why we can’t understand the words of St. Paul. That’s why we can’t understand his exhortation to “deliver such an one unto Satan for the destruction of the flesh, that the spirit may be saved in the day of the Lord Jesus” (1 Corinthians 5:5).

The problem is the one spoken of by Metropolitan Tikhon (Shevkunov):

One day, I was able to pose one and the same question to two different ascetics—Fr. John (Krestiankin) and Fr. Nicholas Gurianov: ‘What is the main illness of contemporary Church life?’ Fr. John replied at once, ‘Unbelief!’ “’How could that be?’ I protested. ‘And what about the priests?’ He again replied, ‘For the priests also—unbelief!’ Then I went to Fr. Nicholas Gurianov, and he gave me the very same answer, independently of Fr. John: unbelief.

The problem is our unbelief. We don’t really believe in Heaven, so we are unwilling to sacrifice our happiness — or the happiness of those for whom we care — on earth. We don’t really believe in the wisdom of the Church, and so we are unwilling to crucify our own understanding. We don’t really believe that God loves us, and so we try to cover over anything in Christianity that doesn’t feel to us like love.

But more than almost anything else: we don’t believe that there is such a thing as a saint.

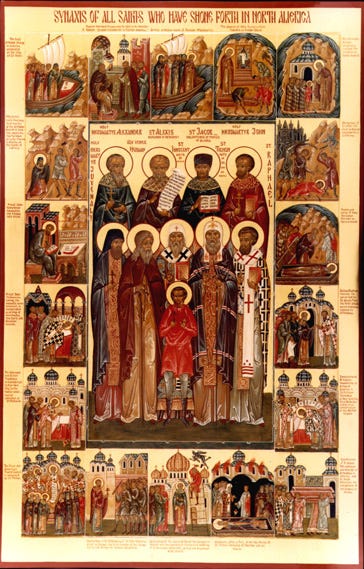

That is what is missing from modern churches: the icons of the men and women who have — in actual reality and even in this present life — been transfigured by the grace of God, and become that which human beings were always truly meant to be.

We don’t believe that we can really become that way: sanctified, purified, transfigured. We are afraid even of the idea of it.

Some of my spiritual children tell me that when they hear the lives of the saints or read their writings and exhortations, they feel overwhelmed and discouraged because they fall so far short of such a standard in their own lives. I usually answer with a metaphor: when we feel like this, we are like a small child who walks into a gymnasium and sees the posters on the wall of extraordinary gymnasts accomplishing incredible feats, and who then becomes downcast and disheartened because they cannot yet do those things. The posters on the wall aren’t there to intimidate us — they are there to inspire us.

We have forgotten how to be inspired by sanctity, and when faced with it we feel only guilt. And so we have taken down the saints’ icons and we have forgotten about their lives, and to make ourselves feel better we have dismissed such things as idolatry, or naïveté, or both. But somehow, I don’t think that we actually feel any better about our lives for having done so.

Because Jordan Peterson said it, as best he could in his secular and psychological and intellectual way: “we’re built for nobility.” What the Christian knows is that we are built for even more than nobility. We are built for sanctity. We are built for divinity.

We are born to become saints.

And here is what Archimandrite Vasileios of Iveron has to say about that:

When we are in the presence of a Saint, he does not make our heads spin with theories. Our minds have become a seething mass of theories, anti-theories, and super-theories. But in the person of the Saint we have before us a true human being, a clear image of God; and the important thing is not what he says but what he imparts through his presence… The Saint imparts something: he imparts the grace of God, which tests man. For those who speak the language of the family, man’s natural language, it is a blessing. And for those who speak the language of self-love and hatred, it is hell. It cannot be otherwise…

But the Saint does not destroy us; he does not use us. He loves us. But do not think that his love is sentimental. It is harsh, much harsher than any cruelty. He wants each of us to be saved, to become god by grace.

The gratitude and reward for him is that we should find ourselves, that we should be sanctified, and that from the depths of our being there should arise the doxology: ‘Glory to God!’ He does not want to make us supporters of his party or members of his association… He only wants us to find our way in Christ Jesus.

Let such a love fill each and every one of us. “It is harsh, much harsher than any cruelty,” but it is the only kind of love that can possibly bring healing and salvation and peace. The world needs such love, now as much as ever. But now, far more than ever, it only has the chance to see such love in the faithful sons and daughters of the Church. Let us therefore beseech the Lord, through the intercessions of His Most Pure Mother and of all the saints, that the world will be able to see such love in us. Amen.

Through the prayers of the Theotokos, Savior, save us.