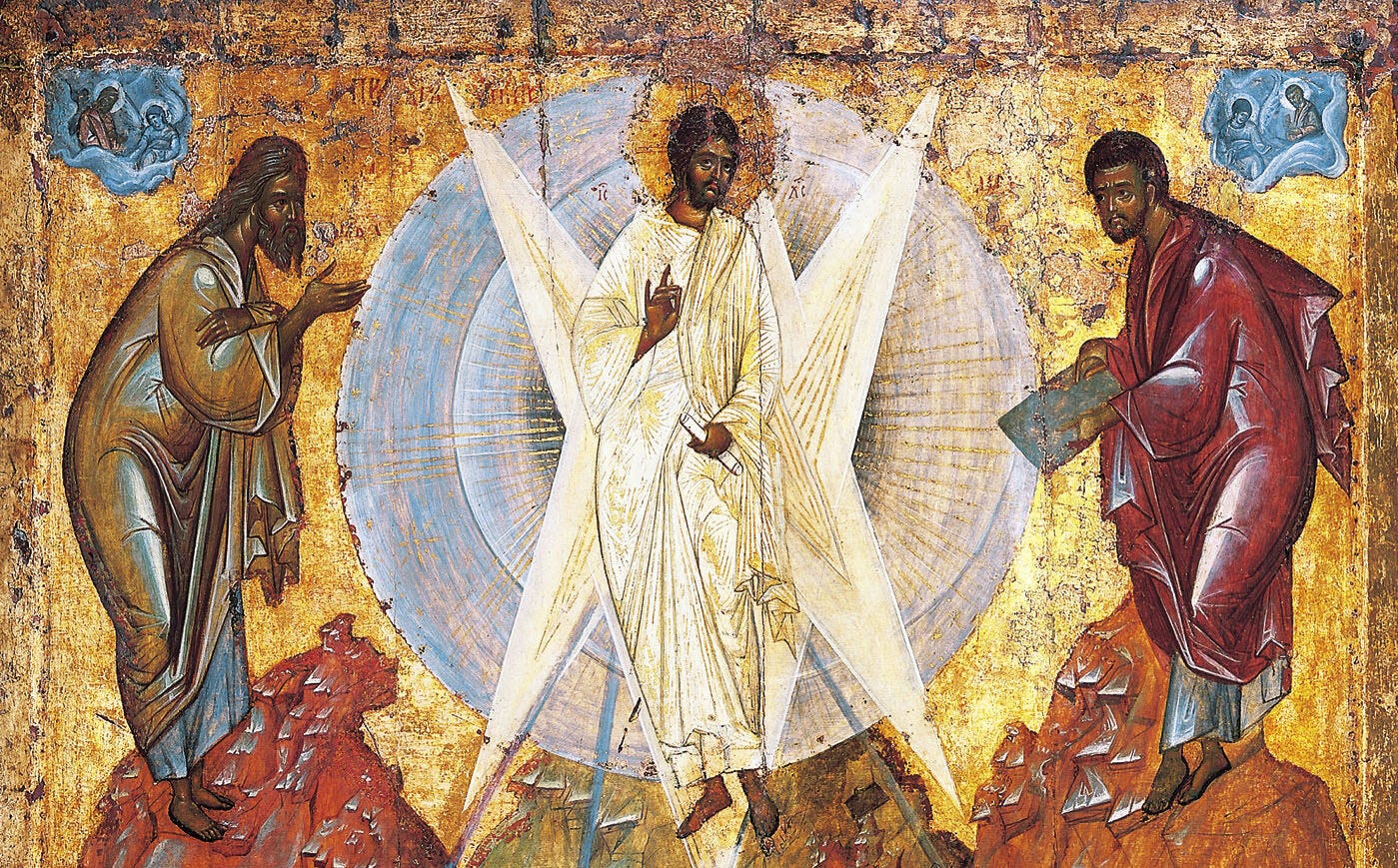

We celebrate today the great and glorious feast of the Transfiguration of Christ. On this day the Lord took three of His closest disciples — Peter, James, and John — up to the summit of Mount Tabor, where He revealed Himself to them in His divine and heavenly glory. St. Peter only one week earlier had, for the first time, openly confessed Jesus as “the Christ, the Son of the living God.” Now the Lord, for the first time, openly reveals the truth of this confession to the bodily senses of the disciples — so far as such a thing is possible. And through their witness, the Church reveals to us today that same glorious truth: that Jesus Christ is indeed the Son of the living God.

When I was a young Christian, having newly made for myself the confession of St. Peter in the divinity of Christ, of course I found this feast to be tremendously inspiring. Through the witness of the Church, I knew that Christ came not only to reveal this glory to His followers, but also to bestow upon them this same glory as well. I listened with longing to the words which St. Peter later spoke, exhorting us to “the knowledge of Him that hath called us to glory and virtue: whereby are given unto us exceeding great and precious promises: that by these ye might be partakers of the divine nature, having escaped the corruption that is in the world through lust” (2 Peter 1:3-4). Yet for all its exalted beauty, there was still something about this feast that puzzled me.

We heard just now in the Gospel reading that, when he witnessed the Lord transfigured in glory before him, St. Peter then “said unto Jesus, LORD, it is good for us to be here: if Thou wilt, let us make here three tabernacles; one for thee, and one for Moses, and one for Elias.” But St. Luke adds that he did not know what he was saying — meaning that St. Peter, having been awestruck by the glorious vision revealed to him, had perhaps spoken such words a bit thoughtlessly.

“But what could be wrong with what he said?” I thought. “He wanted to remain in the presence of Christ, he wanted to forsake everything earthly in order to abide always in the glory of living God. Isn’t that what we Christians are supposed to want?”

And indeed, though all Christians have in some measure experienced such desire, the hard truth is that often our desires are very far from the glory of Tabor. How many of us, if given the chance, would really choose what St. Peter asked for today: to never return to anything or anyone in this world, if only to be able to abide always in the presence of Christ? Though in our best moments I hope that all of us would choose this, yet there are all too many moments in our lives when we would not. And I know this because we are always, at every moment of our lives, being offered such a choice — and so many times we choose instead to return to the people and the places and the things of this passing world. Each and every sin we commit is a proof of this.

I am reminded of a story I once heard about an abbot here in America. One night he was on the subway in New York, traveling back to his monastery from some business in the city. Seeing him in his monastic attire, a homeless man came up to him and began to question him about his faith. The abbot, in the course of answering the man’s questions, began to speak about the mystery of Holy Communion. The pauper then interrupted him: “Wait a minute, you’re trying to tell me you believe that Jesus Christ is physically present with you in your churches?” The abbot, of course, answered that he did believe this, and that even outside of the Divine Liturgy the reserved Holy Gifts are always present on the altar table, and that for this reason Orthodox Christians cross themselves whenever they pass by a church. “There is no way that you really believe that,” the man replied firmly, much to the surprise of the abbot. “And I’ll tell you how I know that you don’t: if I believed that Jesus Christ was physically present in the church where I was praying, I would never leave.”

The sad truth is that many of us Christians — even us monks and us priests — are put to shame by the disbelief of strangers, no less than by the error of St. Peter on this feast.

Nevertheless St. Peter did speak in error, although the Lord did not answer him with a rebuke for this. No, instead of reproaches St. Peter was vouchsafed to hear the very voice of God the Father proclaiming truth and love — just as in our own lives God so often answers our own faults not with punishments, but with even further outpourings of grace.

But my question then remains: what precisely was the mistake that St. Peter had made? Being a young Christian, I had as yet almost no idea of the vast treasuries of insight into the Scriptures offered by the Holy Fathers, who could have quickly and easily answered my simple question. And indeed, I could have even more conveniently found the answer if I had heeded the advice of the then-living Fr. Thomas Hopko of blessed memory, who once said concerning the interpretation of passages of Scripture: “It really helps to read the whole thing.”

Because there is one continuous thread running throughout the Gospel narrative concerning the Transfiguration: from the beginning one week before, when St. Peter first made his confession of faith, to the event itself when Christ conversed in glory with the Holy Prophets Moses and Elias, to the end when Christ descended with the Apostles down from the mountain and back into this sinful world. It is the same thread that runs throughout the whole of the Gospels themselves, and indeed throughout the entire history of the human race: that of “the Lamb slain from the foundation of the world” (Apocalypse 13:8).

As the Gospels state, immediately after St. Peter made his confession of faith in the divinity of Christ, the Lord “from that time forth began… to shew unto His disciples, how that He must go unto Jerusalem, and suffer many things of the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and be raised again the third day” (Matthew 16:21). Even in the midst of the glory of Mt. Tabor, the transfigured Savior spoke with St. Moses and St. Elias precisely “of His decease which He should accomplish at Jerusalem” (Luke 9:31). And afterward, while descending the mountain, the Lord once more impressed upon the disciples how that “He must suffer many things, and be set at nought” (Mark 9:12).

The error of St. Peter was not at all his desire to forsake everything earthly for the sake of the glory of God. His error was in forgetting that although the glory of God may be glimpsed from many places in this world, it can be acquired nowhere other than on the Cross of Christ.

More than this, we might even dare to say that the Cross is itself the glory of God. It was precisely at the hour of His betrayal and death on the Cross that the Lord said: “Now is the Son of Man glorified” (John 13:31). St. Paul, who was transported even in this life unto the third heaven, nevertheless declared: “God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ.” And yes, my brothers and sisters, the glory of God glimpsed today by the Apostles on Mt. Tabor can truly become our own glory… if only we will take heed to the words spoken to them by Christ before He showed them such a glorious vision: “If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow Me” (Matthew 16:24).

Why is it that the Cross is so intimately connected to the glory of God, and to our own salvation and deification in Him? Why is it that Christ had to take up the Cross for us, and why does He insist that we must in turn take up our own cross for Him? The answer is quite simple: because “greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13). St. Isaac the Syrian says that God could have wrought our salvation in any number of ways, but He chose the Cross because it most perfectly manifested the greatness of His love. A love which does not demand, nor does it merely give, but rather offers up everything, unstintingly, even to the point of one’s very own life itself, for the sake of the beloved.

There is nothing, neither in this life nor in the next, which is more glorious than such love. This love caused God to become man, and through this love (and this love alone) man can become God.

Let us listen to the words of the Holy Apostle John, who was also on the mountain this day with Peter and James:

Behold, what manner of love the Father hath bestowed upon us, that we should be called the sons of God… Beloved, now are we the sons of God, and it doth not yet appear what we shall be: but we know that, when He shall appear, we shall be like Him; for we shall see Him as He is… Hereby perceive we the love of God, because He laid down His life for us: and we ought to lay down our lives for the brethren. (I John 3:1-2, 16).

My brothers and sisters, on this holy and glorious day let us long with all our hearts to see the Lord transfigured in His glory. Let us strive with all our souls to be arrayed in this same glory together with Him. And above all, let us on this day remember the true nature of divine glory: the glory of love, the glory of the Cross. Let us then take up our crosses eagerly and joyfully, with fervent love laying down our lives for God and for each and every one of His children whom we meet in this world. Out of love and longing for the glory of Tabor let us kiss the earth of our own personal Golgotha, for as the Holy Elders of Optina remind us (and as even the geography of our own insignificant monastery reveals to us): the only path to Tabor leads through Golgotha.

Let us resolve then to take up this path and to follow it unswervingly, from this very moment until the end of our earthly life, not ceasing until, in the words of St. Paul, “we all, with unveiled face beholding as in a glass the glory of the Lord, are changed into the same image from glory to glory, even as by the Spirit of the Lord” (2-Corinthians 3:18). Amen.

Amen! Very beautifully written, Fr. Gabriel!