As we once again approach the beginning of a new year, it is good for us as Christians to take advantage of this opportunity for self-reflection, to prayerfully reexamine how we are living our lives and whether we are doing so in light of the Gospel of Christ. Indeed, just as we Orthodox Christians pray each evening in the words of St. John Chrysostom: “though I have done nothing good in Thy sight, yet grant me by Thy grace to make a good beginning,” so too we ought to pray in the last hours of the year that is now coming to a close.

But how exactly should we examine ourselves, and how best can we strive — with the help of God’s grace — to make such a good beginning? What does “a good beginning” in the Christian life truly look like? For the answers to these questions, I suggest we meditate first on the beginning of the Gospel itself.

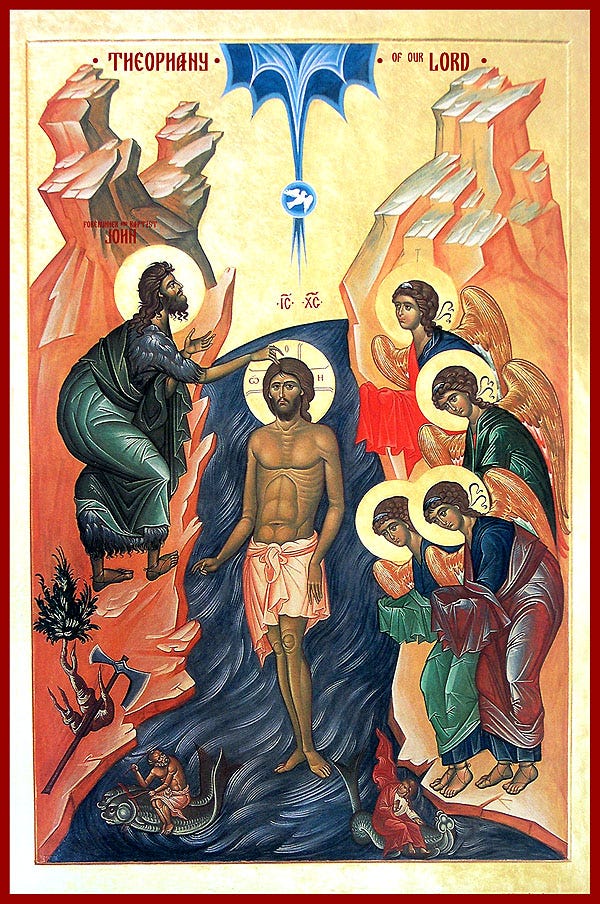

After Christ’s Theophany at the River Jordan (which we will soon once again celebrate) and His forty days of fasting in the wilderness (which we will soon once again emulate in the season of Great Lent), He began His preaching of the Gospel with these words: “Repent: for the kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matt. 4:17). Though these words are extremely well known, they are also extremely poorly understood. Christ did not simply command His people to cease from their sins — as countless moralizers from time immemorial have done. Nor did He merely teach that some vague future bliss awaits the human race beyond the grave — as so many of our contemporaries have reduced our religion to mean. No, Christ instead preached repentance, because the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand.

It is true that we Orthodox are more likely than most modern Christians to understand (at least intellectually) that repentance does not fundamentally mean to feel guilty about our past sins, nor even merely to cease from sinning in the future. Probably we know that the English word “repentance” is a (quite dubious) translation of the Greek word μετάνοια, “metanoia,” meaning literally to change one’s nous — that is, to change our fundamental way of understanding reality. But as Metropolitan Jonah (Paffhausen) once remarked, we modern Americans — regardless of our formal religious affiliation — are all in some sense Southern Baptists. That is, there is a common religious framework that our culture has instilled into our subconscious — and so when we hear Christ and His Church use words like “repentance,” on some deep level we really hear what our culture has taught us those words mean.

And so — no matter how good our intentions are, and no matter how correct our formal theological beliefs may be — when we hear someone like St. Isaac the Syrian say: “This life has been given to you for repentance; do not waste it in vain pursuits,” what we really hear is something like: “You should be spending your entire life on earth feeling bad about yourself instead of having any fun.” It is — to say the least — not the most inspiring philosophy by which to live.

It is not that our cultural conception of repentance is totally wrong; it is more that there is so much that it is missing. And the main thing that is missing is, quite simply, the reason Christ Himself actually gave for it: “the Kingdom of Heaven is at hand.” And He really meant that it is at hand. He did not come simply to explain to us some cosmic legal system of merit-based rewards and punishments, having little to do with the here-and-now and which none of us will actually experience until the afterlife. No, He came to give sight to the blind and life to the dead, “to pour out His spirit upon all flesh” (cf. Acts 2:17).

He came to make us gods by grace.

It is precisely this “change of heart” that Christ came to give freely to mankind; it is precisely this change of being which we have been given our lives on this earth to acquire. And it does not belong simply to some far-removed future age; it begins here and now, with our baptism, just as Christ began His preaching of it with His own baptism. We enter deeper and deeper into this reality with every prayer we utter and with each hymn we sing, and above all at every one of those holiest of moments when we eat and drink the Body and Blood of the God-Man Jesus Christ. This reality, though perhaps invisible to our bodily eyes, nevertheless shines mystically and brilliantly in every church and monastery and icon corner throughout the entire world — no matter how humble or ordinary their outward appearance. And this reality lives and breathes in every single person that we meet — because the truth is that each and every one of us, no matter how ugly and terrible and all-encompassing our sins, nevertheless bears within ourselves the indelible image of God.

None of this is to say that repentance should not be something sorrowful; indeed, how could it not cause the keenest of sorrows to understand how great the riches are which we have squandered (and still squander), and how trifling are the trinkets we have clung to in their place? And yet, along with such sorrow, there must also come overwhelming joy and infinite gratitude when — like the Prodigal Son in the parable — we see our Heavenly Father still rushing out to meet us and embrace us, to clothe us with His finest garments and to give us the best of all that He has, though we have done less than nothing to deserve it, and though we are still so very far away from home.

So it is indeed with sorrow, but all the more with gratitude and joy, that we must make our good beginning of repentance in the coming year, imitating St. Paul who said: “this one thing I do, forgetting those things which are behind, and reaching forth unto those things which are before, I press toward the mark for the prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus” (Phil. 3:13-14). And in another place: “let us lay aside every weight, and the sin which doth so easily beset us, and let us run with patience the race that is set before us, looking unto Jesus the author and finisher of our faith; who for the joy that was set before Him endured the cross, despising the shame, and is set down at the right hand of the throne of God” (Heb. 12:1-2). And finally, let us not cease to keep the joy of the Cross set before the eyes of our hearts “till we all come in the unity of the faith, and of the knowledge of the Son of God, unto a perfect man, unto the measure of the stature of the fulness of Christ: that we henceforth be no more children, tossed to and fro, and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the sleight of men, and cunning craftiness, whereby they lie in wait to deceive; but speaking the truth in love, may grow up into Him in all things, which is the head, even Christ” (Eph. 4:13-15).

For truly, it is “the goodness of God [that] leadeth thee to repentance” (Rom. 2:4); “it is your Father’s good pleasure to give you the Kingdom” (Luke 12:32). Amen.